Seller's Promises Not To Compete or Challenge Reasonableness of Restrictive Covenant Unenforceable

Last week, the Delaware Court of Chancery issued an important opinion for businesses and M&A attorneys crafting agreements with restrictive covenants that purport to bar sellers from (i) competing against buyers and (ii) waiving the right to challenge the reasonableness of the restrictive covenants.

Every deal lawyer should read the opinion. It instructs that restrictive covenants must be tailored to protect a buyer’s legitimate business interest in the purchased company or assets, not a buyer’s pre-existing business or assets. And a seller’s promise in a purchase agreement not to challenge the reasonableness of a restrictive covenant is now effectively worthless under Delaware law. Delaware courts will always review a restrictive covenant for reasonableness as a matter of public policy.

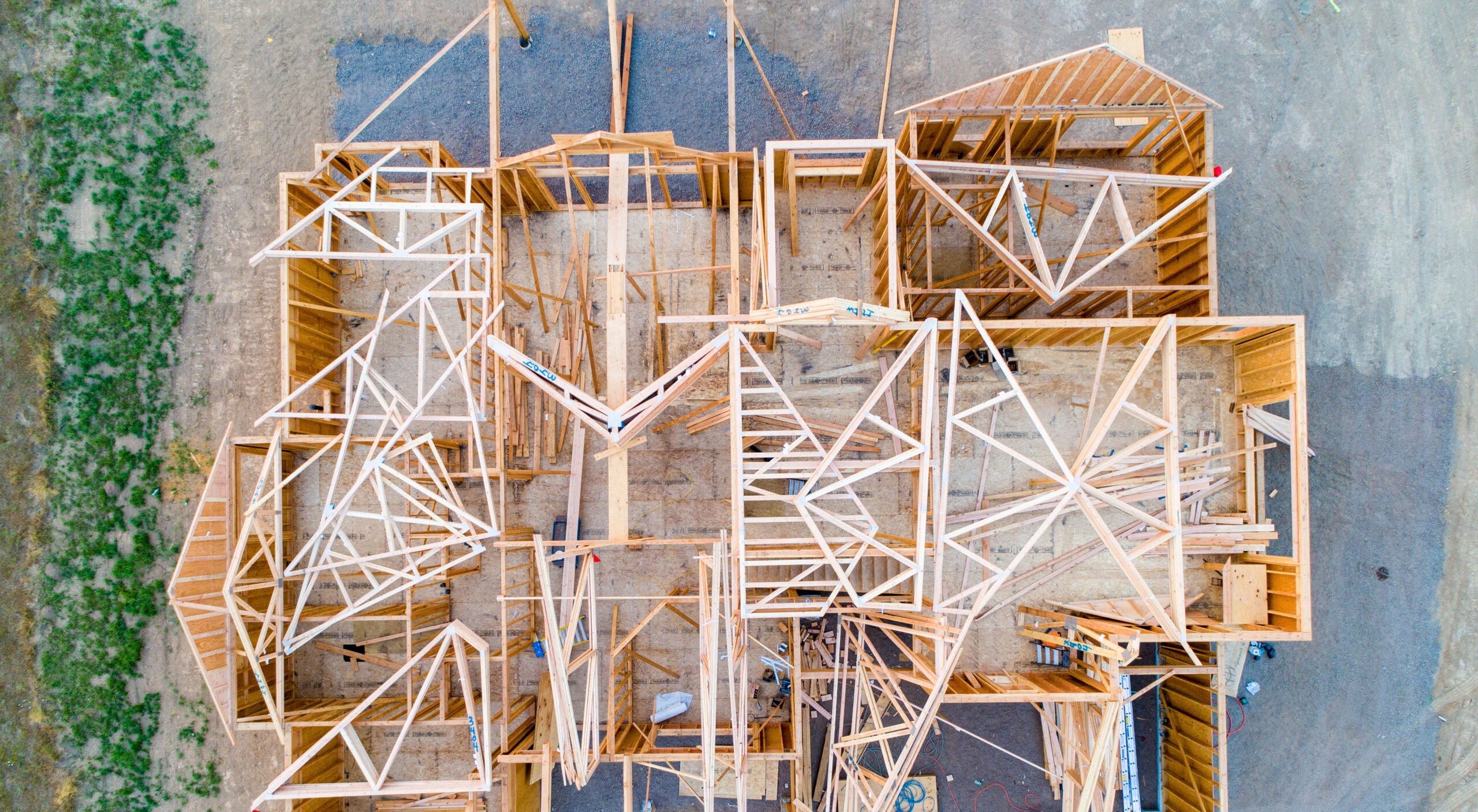

The case is Kodiak Building Partners, LLC v. Adams, C.A. No. 2022-0311 (Del. Ch. Oct. 6, 2022). The buyer (Kodiak) is a Delaware limited liability company. For several years, Kodiak has been on a nationwide buying spree acquiring small companies in the construction industry. Kodiak’s portfolio included companies specializing in lumber and building materials, roof trusses, wall board, construction supplies, and kitchen interiors.

On June 1, 2020, Kodiak entered into a stock purchase agreement to buy Northwest Building Components (NBC). NBC operated out of a single location in Rathdrum, Idaho. NBC manufactured and sold roof trusses and other lumber-based building products used in framing and new construction. One of NBC’s sellers was its general manager, Philip Adams, who owned 8.3% of the company and oversaw all of NBC’s day-to-day operations. Adams received just under $1 million from Kodiak as a result of NBC’s sale.

As part of Kodiak’s acquisition, Adams agreed not to compete against Kodiak or solicit Kodiak’s customers. Adams’ restrictive covenant ran for 30 months from closing. Adams promised not to compete with any of Kodiak’s portfolio companies within the states of Washington or Idaho or within a 100-mile radius of any other Kodiak company location. Adams also promised not to solicit any of Kodiak’s portfolio companies’ prospective clients or customers.

As part of the stock purchase agreement, Adams also agreed that “each restraint in this Agreement is necessary for the reasonable and proper protection” of Kodiak’s acquired assets. Adams explicitly waived his right to challenge the reasonableness of his restrictive covenant.

Adams resigned from NBC four months after the closing and took a job with Builders FirstSource as its general manager in December 2020. Builders FirstSource, located twenty-four miles away from NBC’s headquarters, had a national roof truss business supplying lumber, roof trusses, and design services. Builders FirstSource competed directly with NBC. NBC learned of Adams’ new position when it began losing jobs as a result of Adams’ work for Builders FirstSource. NBC sued Adams in Delaware and sought a preliminary injunction to enforce his restrictive covenant.

Delaware courts “carefully review” restrictive covenants to ensure they are reasonable as to geography, scope, and time. Restrictive covenants must advance a legitimate economic interest of the party seeking enforcement. The Kodiak court recognized that “covenants not to compete in the context of a business sale are subject to a ‘less searching’ inquiry than if the covenant ‘had been contained in an employment contract.’” Nevertheless, the court proceeded to scrutinize Adams’ non-compete closely.

Kodiak first argued that the Court of Chancery should not review the restrictive covenant for reasonableness because Adams explicitly waived that defense in the stock purchase agreement. The court acknowledged no other Delaware opinion directly addressed this argument. After analyzing the issue, the court determined that “an employee’s promise not to challenge the reasonableness of his restrictive covenant cannot circumvent this court’s mandate to review those covenants for reasonableness.”

The court then proceeded to review the reasonableness of Adams’ restrictive covenant. The court emphasized that “[i]n the context of a sale of a business, the acquirer has a legitimate economic interest with regard to the assets and information it acquired in the sale.” Kodiak argued Adams’ restrictive covenant was reasonable because it had a legitimate interest not only in NBC’s goodwill but also that of Kodiak and its other portfolio companies. The court rejected this argument. It held that an “acquirer’s valid concerns about monetizing its purchase do not support restricting the target’s employees from competing in other industries in which the acquirer also happened to invest.”

It then naturally followed that the court found the restrictive covenant to be unreasonable both in its geographic scope and the scope of restricted activities “because they are broader than necessary to protect Kodiaks’ legitimate economic interest.” The court denied Kodiak’s motion for preliminary injunction, and Adams was allowed to continue working as Builders FirstSource’s general manager.

Key Takeaways:

- In most purchase agreements, sellers’ acknowledgments about the reasonableness of restrictive covenants are boilerplate. They are commonly seen in almost all deals. If Kodiak stands, that language is probably now pointless if a dispute later arises. Delaware courts will prioritize the public policy of encouraging competition and taking a critical eye toward non-competes. As the court stated: “Even if Adams had not briefed his position that the [restrictive covenant] was unenforceable, I would still have to comply with Delaware law and review [it] for compliance with public policy before enforcing it with an injunction.” In any restrictive-covenant fight, a Delaware court will conduct a reasonableness inquiry sua sponte.

- The Court of Chancery acknowledged the novelty of this issue. No other Delaware court has previously addressed a similar contractual term. Kodiak’s argument has solid appeal from a pure “contractarian” position: Adams willingly entered into the restrictive covenant, agreed to its terms, accepted $1 million, and should be held to his bargain. This case is worth monitoring if Kodiak appeals to the Delaware Supreme Court.

- As businesses and private equity firms roll up different industry sectors, these types of restrictive covenants seeking to protect a wide variety of business interests are likely to be common. We’ve seen similar types of broad, all-encompassing restrictive covenants that purport to bar large swathes of activity in numerous geographic areas. Be wary. Competition and encouraging employee mobility are the name of the game nowadays. At least in Delaware, the key interest at stake is the acquired assets, not the buyer’s already existing businesses and assets.

- Don’t rely on blue-penciling. If the court wanted to, it had the power to alter the restrictive covenant’s scope and impose a “reasonable” set of restrictions on Adams (so-called “blue-penciling”). The court declined to exercise that authority. Don’t assume a court will save an overly broad restrictive covenant by imposing reasonable conditions.

- Don’t over-reach. If Kodiak had not over-reached initially, it probably could have precluded Adams from working at a direct competitor just 24 miles away from NBC. Kodiak could have told Adams: don’t work for a competing roof truss company within 50 or 100 miles of NBC for two or three years. And that would almost certainly have been enforceable. But because Kodiak insisted on a much broader set of restrictions, Adams is free to compete and take Kodiak’s customers. Prohibit only what you need. Otherwise, you run the risk of having no competitive protections.

In This Article

You May Also Like

Federal Trade Commission Bans Noncompetes DC Circuit Demands Clearer Definition of “Critical Infrastructure”