Structural Obviousness Receives a Boost at the Federal Circuit

“When compounds share significant structural and functional similarity, those compounds are likely to share other properties….” This was the premise behind the Federal Circuit’s validation on April 8 of a prima facie case of obviousness of a formulation patent claim in a Hatch-Waxman case.

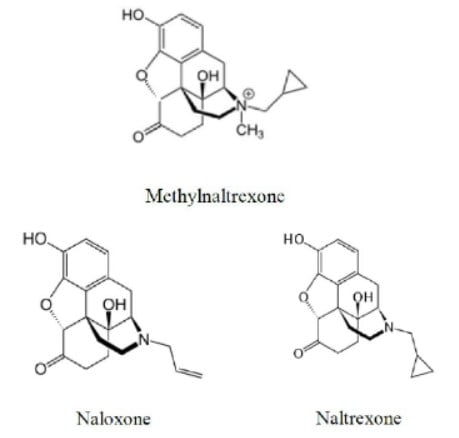

The case involves Relistor® (methylnaltrexone), a drug used to reduce certain side effects of opioids. The patent claim-at-issue is directed to a methylnaltrexone composition rendered stable by maintaining an acidic pH between 3 and 4. The prior art teaches:(i) stable solutions of the structurally related compounds naloxone and naltrexone with pH ranges overlapping with the claimed range; and (ii) pH as an important factor generally in determining a composition’s stability.

The district court granted summary judgment of no obviousness to the patent holder. According to the district court, the prior art would not have motivated a skilled artisan because the art pertained to different compounds, not methylnaltrexone. Moreover, in the district court’s view, the claimed pH range would not have been obvious to try because the quantity of number ranges between pH 3 and 7 were “infinite, not finite.”

The Federal Circuit reversed, explaining that “[b]ecause of the strong structural and functional similarity between the molecules, a person of skill could expect similar stability of the molecules at similar pH ranges in solution.” That is, the stability of methylnaltrexone at the pH range 3 to 4 was a predictable result, according to the Federal Circuit, and the generic challenger established a prima facie case of obviousness sufficient to defeat summary judgment. The court explained the structural similarity principle by addressing the structural similarities between methylnaltrexone and the prior art compounds (shown in the diagram above) and surveying prior cases involving compound and method-of-use patents that turned on structural and functional similarities between the claimed and prior art compounds.

The Federal Circuit also held that the district court’s obvious-to-try analysis was grounded in error: “[T]here is only one significant figure after the decimal point, in which case the range of pH variables is ten, or, if one considers two significant figures after the decimal point, one hundred, not an infinity.” Put another way, the prior art presented a finite number of predictable pH ranges to try, rendering the claimed pH range obvious to try. The court thus reversed the grant of summary judgment and remanded.

Upon returning to the district court, the focus will be on whether the patent holder can successfully rebut the prima facie case of obviousness by arguing, for example, that the claimed pH range was critical or secondary considerations imparting patentability, such as unexpected properties.

The court’s recognition that “[w]hen compounds share significant structural and functional similarity, those compounds are likely to share other properties including optimal formulation for long-term stability” will likely spur additional structural obviousness challenges against pharmaceutical patents.

The case is Valeant Pharmaceuticals Int’l Inc. et al. v. Mylan Pharm. Inc., case number 18-2097, in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The case below is Valeant Pharm. Int’l, Inc. v. Mylan Pharm., Inc., No. CV 15-8180 (SRC) in the District Court of New Jersey.

If you have questions about how this decision might affect your business, please contact the authors or a member of the Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences Litigation practice.

In This Article

You May Also Like

Writing Strong Antibody Claims: Avoiding or Addressing USPTO Rejections for Written Description and Enablement Reconsidering IPR Strategies in Light of Kroy IP Holdings v. Groupon